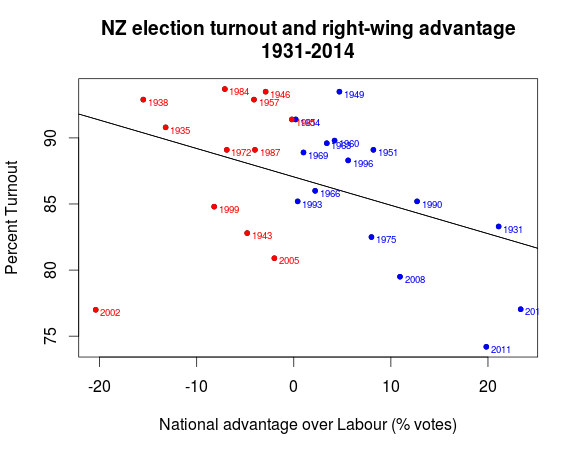

Psychologists and political scientists have studied voter turnout and identified social pressure and identity as some of the strongest factors which can be changed to influence people to vote. In New Zealand, voter turnout in 2011 since before voting was extended to women in 1893!

Voter turnout varies a lot from one election to the next and can be quite important in determining election outcomes. Changes in voter turnout can be much larger than the margin by which a new government wins office. For instance, in the New Zealand general election in 2011, the governing and supporting parties (National, Maori, ACT, and UF) won 93,939 more votes than the opposition parties (Labour, Greens, NZ First, and Mana) in Parliament

[1]. Turnout had dropped from 79% in 2008

[2] to only 74% in 2011, which was an absolute difference of 177579 extra voters who were eligible to vote and didn't – in other words, if just the voters who had voted in 2008 election had all voted in 2011 (not including the 20% of eligible voters who didn't vote in either election), they could have changed the election outcome!

| Party group |

Votes |

| Government (National, etc) |

1127950 |

| Opposition (Labour, etc) |

1034021 |

| Difference |

93929 |

| Year |

% Turnout |

Non-voters |

| 2008 |

79% |

614279 |

| 2011 |

74% |

791858 |

|

-5% |

-177579 |

This makes turnout potentially an important decider in elections. Historically, political campaigners know this and have spent a lot of energy either trying to convince people to vote in Get out the Vote campaigns, or - arguably - trying to discourage people from voting with poll taxes, voter ID laws, etc.

Behavioral researchers have examined the design of elections and how the design of an election could encourage or discourage people to vote, and also tactics which political campaigners might be able to use to encourage people to vote.

Exploring social influence: Bischoff & Egbert

[3] wrote about how people choose a candidate, not about turnout in general, but the principles could apply to deciding whether to vote at all, as well as deciding to vote for a particular candidate. People might look to others in their social group or other people like them as a guide for picking the best candidate, particularly if they're not confident of being good judges at that. People could also follow their peers not because they necessarily thought their peers were good at picking good candidates but simply to fit in with their peers. People might also want to vote for the candidate they thought would win, regardless of whether they really preferred the candidate because either they just want to reduce uncertainty or to reduce future anxiety from seeing their candidate lose and having to confront the idea the “worse” candidate won.

Identity as a voter: Christopher Bryan and colleagues

[4] at UC-Irvine found they could influence voting by surveying voters about “being a voter” or simply about “voting”. They thought that a person's identity is important to them, that in general, people believe voting is a positive thing or a moral good or at least a civic duty, and so that if they prompted people to think about voting as an identity “being a voter”, people would prefer to claim that identity for themselves in order to improve their image or their identity. Conversely, if people were asked about voting, they'd be less likely to think of being a voter as an identity and so being motivated to improve their image and identity wouldn't lead them to vote. People actively manage their self-concepts and try to improve it by doing things which improves their self-concept – if surveyors suggest that “being a voter” is relevant to an identity, it becomes more relevant to participants' self-concept.

Social pressure also seemed to help – a little bit. In elections in New Jersey (2005) and California (2006)

[5], people were given information over the phone either that voter turnout was low and declining, or that it was the highest it has ever been. They were later given a survey asking them about their likelihood of voting. Across the two experiments, prospective voters were on average about 4% more likely to say they would definitely vote when they were told voter turnout was at record highs than when they were told it was declining.

Another study

[6] didn’t find that telling people about turnout in their own community influenced turnout, but reminding people that their vote was a matter of public record – displaying whether they voted previously – did significantly improve turnout. Even thanking voters

[7] for voting via a mailout produced a significantly higher turnout in the next election, compared to voters who got a generic reminder mailout which didn’t thank voters for voting previously.

Self efficacy and socioeconomic status: One unexpected finding came from a study

[8] comparing 18 and 19 year old first-time voters, split into two groups depending on whether the voter had a

mother who graduated from high school. It seems like a strange thing to look at, but researchers used mother’s education as a general, rough measure of someone’s socioeconomic status. It turned out that 43% of young people with a high school graduate mom turned out to vote while only 29% of young people whose mom didn't graduate came to vote on the day. The same study found 'general self efficacy' predicted how likely young people were to vote,

especially when they came from those disadvantaged backgrounds. 'General self efficacy' is a measurement of how much people agree with general statements like:

“I

can do just about anything I really set my mind to.”

“I

can solve the problems I have.”

Only about 2 of every 10 young people from those disadvantaged backgrounds voted if they were in the lowest 25% on the self efficacy scale, but that proportion rose to 3 or 4 in 10 for the highest 25% on the self-efficacy scale. From 2 to 3 or 4 out of 10 might sound like a fairly small increase but it represents an increase in turnout by an extra half or even doubling of the low-efficacy group.

This leads to an open question – is efficacy something we can induce in prospective voters in this case? Not only does it increase turnout, but stronger efficacy in general seems to be

particularly helpful for young people from disadvantaged backgrounds. So finding ways to increase efficacy – even if it is domain-specific to voting – could be particularly effective in addressing social disparities in voter turnout.

It's really striking how much intergenerational influence could potentially affect an entire generation’s ability to have their civic voice heard in elections.

Voter turnout is a problem of motivation and a desire to change an election outcome, in itself, might not be the most powerful motivator to vote for an individual. Many voters probably understand that individually, their vote is highly unlikely to change the outcome of an election, yet because of social norms about voter civic duty, social pressure, peer influence, and gratitude and other psychological factors which can be influenced by even by a voter’s mother’s education, can play a part in getting voters out to vote. Getting voters to vote as a way to make a statement or feel good about participating in a civic duty may be a much more effective way of motivating voters than simply informing them of the issues at stake.

References

[1]

http://www.electionresults.govt.nz/electionresults_2011/e9/html/e9_part9_1.html

[2]

http://www.electionresults.govt.nz/electionresults_2008/e9/html/e9_part9_1.html

[3] Bischoff, I. & Egbert, H. (2013). Social information and bandwagon behavior in voting: an economic experiment.

Journal of Economic Psychology, 34:270-284.

[4] Bryan, C. J., Walton, G. M., Rogers, T., & Dweck, C. S. (2011) Motivating voter turnout by invoking the self.

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. doi:10.1073/pnas.1103343108.

[5] Gerber, A. S., & Rogers, T. (2009). Descriptive social norms and motivation to vote: Everybody’s voting and so should you.

The Journal of Politics, 71(1), 178–191.

[6] Panagopoulos, C., Larimer, C. W., & Condon, M. (2013). Social pressure, descriptive norms, and voter mobilization.

Political Behavior: doi:10.1007/S11109-013-9234-4.

[7] Panagopoulos, C. (2011) Thank you for voting: gratitude expression and voter mobilization.

The Journal of Politics, 73(3):707-717.

[8]

Condon, M. & Holleque, M. (2013) Entering politics: general self-efficacy and voting behavior among young people. Political Psychology, 34(2): ddoi: 10.1111/pop.12019.